|

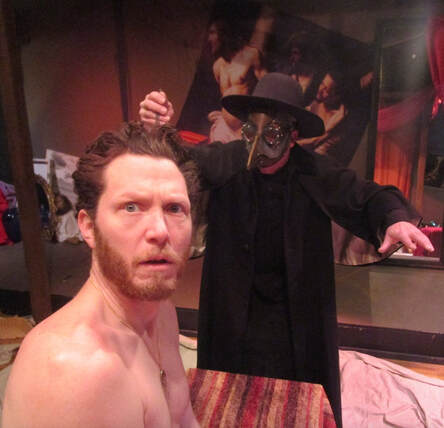

Off the Wall Theatre explores art and truth in an ambitious drama on its cozy, little stage late this Winter. Director/playwright Dale Gutzman’s The Glance rumbles through the Renaissance in a dramatically unflinching look at the life of Italian painter Caravaggio. The action plays out in the cluttered, little studio of the painter as he engages with commercial concerns in the era of the Bubonic Plague. Life and death hang on every edge of the drama as the painter is forced to deal with compromise in the interest of survival and possible fame as balanced against artistic integrity and an open embrace of reality through art. Over the years, Dale Gutzman’s writing/directing work has been hit-or-miss. Without question, The Glance is a hit. Gutzman shrewdly brings four central characters to the stage who are all intensely interesting. Four very talented actors give Gutzman’s script a complexity that makes for a deeply engaging drama. Max Williamson is ruggedly charming as Caravaggio. He’s a man who could become a towering legend if only he were to compromise a bit. Williamson cleverly wields a canny respectability about him that edges occasionally in the direction of madness as artist grapples with the very nature of truth. Caravaggio’s art is cast against that of his brother Giovanni, who makes a similarly artistic living through carnal passions. Nathan Danzer breathes depth into an ambivalent man who finds himself harnessed into something more serious by chance and circumstance. Danzer and Williamson have a strong fraternal connection as the two brothers in a dynamic that is central to the whole drama. Randall T. Anderson adds contrast to the fraternal love in the role of Father D’Angelo. He’s plague doctor who also serves as an aid to the Cardinal. Anderson imbues the character with an appealing personality through a rather dramatic character arc. What opens as a casual interest in Giovanni turns into something more as he is forced to question his thoughts on love and carnality. Gutzman has D’Angelo navigating through a massive shift in personality in the course of the play. This would be challenging enough for any actor. D’Angelo is only a peripheral character, which makes the dramatic transformation all the more difficult. Anderson handles it with a clever wit, tactfully muting some of Gutzman’s more leaden dialogue while accentuating some of the more sophisticated bits of intricacy Gutzman has written into the character. Michael Pocaro rounds out the cast as Caravaggio’s patron Archbishop Borromeo. Pocaro is forcefully charismatic as a holy man desperately trying to understand the mind of God through a deeper understanding of Christ’s suffering. Borromeo is a deeply flawed man. Pocaro approaches the role with respect and sympathy that results in a nuanced portrayal of a man afflicted with his some of the very hubris he is looking to conquer in Caravaggio. The Cardinal could give the artist the fantastic life of a wealthy artist if only he were to soften-up the carnal reality of his paintings. (And maybe get rid of the dog in that painting of John the Baptist.) Pocaro and Williamson are cleverly poised in an intellectual battle of wills that echoes struggles that have been going on between art and authority since the dawn of time. The central themes of The Glance have been resonating through drama forever. Gutzman’s gaze into the struggles of a single artist are haunting at times. At other times they’re a weak echo of an endless struggle. The script is at its best when actors are allowed to dive directly into the struggle between each other without too much intellectual or historical ornamentation. Thankfully, most of the script allows for direct dramatic clashes between strong-willed characters. It is in those clashes that The Glance finds its greatest power. Off the Wall Theatre’s The Glance runs through March 8th at the theatre on 127 E. Wells St. For ticket reservations and more, visit Off the Wall online.

0 Comments

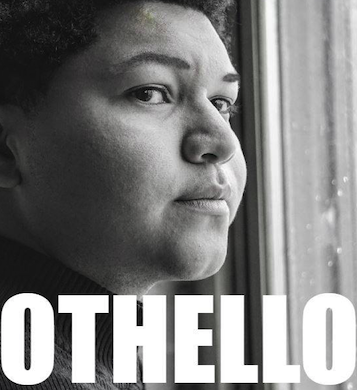

Traditional folklore doesn’t exactly have a reputation for dispensing valuable lessons about the “real world.” In the modern world, fairy tales are generally synonymous with fanciful magic in simple realms of good and evil. As Winter becomes Spring, First Stage presents a small stage fairy tale for kids 8 years and older that goes beyond overly simplistic good-vs-evil themes to cover a huge range of different issues including the death of a parent, being forced to do things against one’s wishes and even the sometimes ambiguous nature of human morality. Based in part on Slavic legend, the folk-rock musical Gretel! follows a young girl into the woods to search for the mysterious being known as Baba Yaga. Her mother has passed away and her father has remarried. Now Gretel has to contend with as wicked stepmother and stepsister who force her to do all the work and demand that she steal magic from Baba Yaga in order that they may have food and light. In order to get what she wants, Gretel must work for Baba Yaga, who slowly teaches her magic, forcing Gretel to wonder wether the sinister witch is truly evil or something else altogether. Can she really be that bad if she's sharing her magical knowledge? This isn't some cheery, little Hogwart's with classrooms and teachers and lessons, though. Baba Yaga is a very cunning and demanding mentor who leads Gretel to some pretty shadowy places. Natalie Ford has wit and wisdom about her in the role of Baba Yaga. There’s a playful darkness about her that seems at once completely honest and completely whimsical. Gretel doesn’t know whether or not to trust her. This could have been terrifying if allowed to develop in a dark direction, but Ford keeps it firmly rooted in a sense of fun and mystery that keeps the mood of the play firmly rooted in drama and solidly removed from realms of nightmare. Max Mainwood is versatile in a few different supporting roles. He’s a flaky, well-menaing father who trusts his daughter to a new wife he hardly knows. Mainwood also picks up rake and broom in the role of Stepmother and Stepsister as well...effectively selling the idea of a number of other characters with subtle, abstract props and without the benefit of a single costume change. Ford and Mainwood are joined by a group of kids in one of two different casts. Kids play Gretel herself, a girl, a boy and a cellist. The cellist joins Ford and Mainwood on acoustic instruments that perform some remarkably high-energy folk rock that’s been written specifically for the show. Scenic Designer Sarah Hunt-Frank has done a brilliant job putting together a very engagingly abstract, little set for the musical. A big, fantasy story featuring moody magic set in the woods might seem ill-suited for the intimacy of a small stage, but Hunt-Frank plays with the wooded imagery in simple, flat planes and cylinders that cleverly calls to the primal aesthetics of a target audience raised with iconic interactive emulations of nature like Minecraft and Roblox. Just to look at it, the simplicity of what Hunt-Frank put together for the stage here would seem a little too quaint to be appealing, but for a generation that’s increasingly interacting in little worlds like this on small glowing screens, it works. Hunt-Franks work here is actually a very, very savvy way to engage kids aesthetically in this kind of cozy, little show. The iconography is very abstract, but it’s appealing. Stepmother appears onstage as a wooden rake. The stepsister is represented by a wooden broom. The mystical knight of night is a bucket and a sash. It doesn’t sound like it should work, but it does. And it does so beautifully. (Days after attending the musical, I showed my daughter a picture of a classical wooden rake and we both laughed thinking about the stepmother. It's sharply minimalist design work.) The most appealing, little bit of design work comes in the form of a magical, little boy doll given to Gretel by her late mother. It’s a stylized classical outline of a paper doll-like boy made of fabric. It’s just abstract enough to be cute and just articulate enough to bring a really cool, little emotionally expressive magical character to the small stage. In a show like this, it’s the tiniest things that can make for the biggest magic. First Stage’s Gretel! runs through March 22nd at the Milwaukee Youth Arts Center on 325 W. Walnut St. For ticket reservations and more, visit First Stage online. As February draws to a close, Mad Rogues presents an intimate, little studio staging of Shakespeare’s Othello performed without all the usual props and lighting and sound design and scenic design and costuming. Without any other distractions AT ALL, director Bryant Mason focusses the show on some remarkably stunning acting. A cast of actors approach the material from a very organic place that moves the tragedy briskly across the stage in a deeply satisfying production. Izaiah A. Ramirez is a warm, articulate presence onstage. There is not menace or malice about him at all. There’s no sense of danger at all about the guy playing Othello in THIS production, which makes the tragedy of his sensitivity all the more crushing. The danger in playing Othello with this much sensitivity lies in the disconnect when the villain Iago awakens suspicion in him. Play Othello too much like a nice guy in the beginning and you run the risk of making the suspicious menace of Othello at the end of the play coming across like a COMPLETELY different character. Ramirez deftly manages an arc that manipulates the joy of emotional sensitivity at the beginning of the play and mutates it under the influence of Iago to the horror of emotional sensitivity at the end of the play. It’s a really refreshingly dynamic take on the character that Ramirez handles perfectly. There’s great heroism in Caitlyn Nettesheim’s performance as Othello’s wife Desdemona. She’s bravely chosen new romantic love over her family’s old, conditional love. When a confidant and longtime friend of Othello’s stands disgraced, Nettesheim brings out the beauty of Desdemona’s selflessness. When her husband’s sensitivity turns to ill-temper, Nettesheim amplifies that selfless heroism in aiding a newfound friend in his quest to regain the trust of her husband. Nettesheim’s Desdemona is refreshingly inspiring. Ken Miller's approach to the villain Iago is a pleasant alternative to the political villainy out of the White House and the Senate in the recent months. Contemporary U.S. politics is a theatre of villainy through childish bully brutality. As cleverly as he is written, Iago can sometimes make it to the stage with a menace that feels a bit childish around the edges. Miller plays to the intellect of the character without distraction. Politics for Miller’s Iago aren’t for the pleasure of personal gain...they’re a game. Miller’s Iago might be casually playing with people’s lives or he might be playing a multiplayer online game. All of the obstacles that line his path are problems to be solved for nothing more than the satisfaction of seeing his vision happen...which fits in impressively-well with what Shakespeare put on the page centuries ago. Marcel Alston is given the unenviable task of playing Othello’s friend Cassio. Shakespeare gives the actor playing Cassio a hell of a lot of ground to cover in a relatively short span of time onstage. Alston breathes the complexity of a full personality around the edges of the dialogue. The script gives Cassio passion, duty, responsibility, irresponsibility, anger a few other things that all have relatively important roles to play in the tragedy. It's a weird scattershot for any actor to try to hit all of that cohesively without a whole lot of fluid time onstage. Alston cleverly strings it all together in a performance that speaks to a depth that might have come from an entirely different play focussed entirely on Cassio. In my experience, Iago’s wife Emilia doesn’t traditionally make much of an emotional impact on the stage until the end of the play. Brittany F. Byrnes puts together a take on the character that is that much more engaging from the beginning to the end of the play. More than just an unwitting pawn for her husband, Byrnes brings the personal day-to-day life of the character a lived-in presence that makes her lack of suspicion for her husband that much more respectable. Byrnes gives Emilia her own life, so it's understandable that she wouldn't see her own husband's villainy even though it IS the center of all the action in the drama everyone in the audience is actively watching. Roderigo is another character who often comes across as a witless pawn of Iago. Rather than going against the grain on this, Simon Earle has been allowed to play-up the character’s fragility as comic relief from the darkness lying in the heart of the rest of the play. And rather than amplifying that fragility in an exaggerated clown-like manner befitting the circus or the current Oval Office, Earle brilliantly plays the comedy of the character in impressively subtle sighs and sags that are all delivered with head-spinning precision. Earle is comic relief, but he’s playing it in a way that is carefully calculated not to overpower any other part of the drama. Reva Fox lends respectable structure to the edges of the ensemble as Desdemona’s father Brabantio. Emmaline Friederichs is suitably seductive as Cassio’s love interest Bianca. Friederichs’ thoughtful sensuality adds a layer of depth to a production that is successful on a great many levels without the benefit of all the other non-acting stuff that can distract from a well-written script. Mad Rogues’ production of Othello runs through Feb. 22nd, 24th, 27th, 28th and 29th at the Marcus Center or the Performing Arts’ Studio 4A on 929 N. Water St. For ticket reservations and more, visit Mad Rogues online. Every now and then a touring show rolls through the Marcus Center that doesn’t get nearly as much attention as it should. The big budget shows blast theeir way across the main stage making way too much money and tiny, little touring acts of far greater substance get ignored altogether. Thankfully, there was a respectably sizable crowd at the Marcus Center’s Vogel Hall for dancer Jade Solomon’s one-night-only public Milwaukee performance of Black Like Me: An Exploration of the Word Nigger. A series of short narrative dances were punctuated in the middle and at the end with a couple of conversations about the nature of the word. The latest performance in Jade Solomon Curtis’ tour was at times deeply moving and disturbingly thought-provoking. The show opens with delicate movements against a large video projection featuring an aerial shot of wind through tall grasses. There was a serene warmth in the visuals accompanying slow, hopeful music while a snowstorm whipped around in the Milwaukee winter evening outside the venue. The simple summery movements of tall grasses in the background establish the immensity of the backdrop the dancer is working with. It’s a nice place to start in a journey that jolts over into some deeply disturbing territory. The video screen behind Solomon is a large wall of visuals that also act as interstitial extensions on the theme. Some of the visuals are more powerful than others. It's particularly disturbing to see dash-cam footage of cops being overtly racist on a screen that large. Anatomy of a Moment: Colored on the Wall Disturbing shock isn’t the sort of thing often played on in small stage theatre. It’s difficult to get an overwhelming visceral jolt to come across in the context of a performance. When it’s carried across with the kind of power Jade Solomon is working with, it can be very powerful stuff. The second piece on the evening is “Colored on the Wall.” Jade Solomon Curtis appears in a neon green hoodie and baggy shorts of the same color which glow dazzlingly in Reed Nakayama’s cool blue light. Solomon Curtis’ balletic hip-hop dance movements assert themselves with inspiring power and confidence that never quite edges over into aggression or violence. Solomon Curtis glides across the stage with a beautifully graceful dominance amidst techno beats from VIBEHEAVY. Solomon is a beautiful silhouette in radiant green. It's hypnotically gorgeous stuff amidst moody dance music until the boom is lowered in a powerfully visceral emotional gut punch. The dancer hits the ground screaming. The music switches to the upbeat power of the Otis Day and the Knights’ celebratory 1978 cover of “Shout.” The massive video screen backdrop explodes in lightly animated archival photos of blacks hung from trees. The video has the tragic victims from those old photos slowly swaying amidst the upbeat celebration of Otis Day while Solomon screams. The layering of scream, upbeat music and grizzly images from history had me picking my jaw up off the floor. In ten years of going to over 1100 shows, I can scarcely remember a more viscerally jarring moment in a theatre seat. This sort of emotional assault is attempted so rarely and it’s so rarely done well. I’m still getting chills writing about that moment, which will likely haunt me through the rest of the winter. Other Moments Jade Solomon dances with a lot of other weighty themes in the course of the program. “A Star Named Nigga,” analyzes the stereotype of hip-hop culture with Solomons’ distinctly precise and passionate balletic fusion. “Under Fire” is an exploration into aggression and self-destruction. The dancer’s passion and intensity are strikingly unflinching. Direct Discussion in Two Parts It’s all abstract movement except for the conversations. There’s one in the middle of the program and a more traditional talkback at the end of the show. There’s a kind of fearlessness in holding something that feels like a talkback in the middle of a program...but it’s more than that. Local talent and others including educator Walter Beach III and the show’s sound designer DJ Topspin discuss the word at the heart of the program. Mics are available to the audience to join-in the discussion. It may be obvious that the word is vulgar and oppressive regardless of who speaks it, but there ARE more complex issues that make an open discussion of the word an interesting exercise at times. The Marcus Center performance of Black Like Me is the last date listed on Jade Solomon’s tour schedule. For more information, visit Jade Solomon Online. Cabaret Milwaukee makes a classy splash into February with a swinging retro variety show. Cream City Crime Syndicate: Ransom is Relative continues the group’s heroic historical serial about Milwaukee’s Mayor Daniel Hoan in an era of prohibition and organized crime. Cabaret Milwaukee’s mix of music, comedy and hardboiled action drama feels a bit more balanced than it has in the past. The large ensemble brings a diverse and complex retro world to the historic space of the Astor Hotel bar.

Tall, smooth Marcus Beyer plays classically poised radio host Richard Howling. Once again he introduces the show and welcomes the audience back from intermission with the velvety jazz of crooner Cameron Webb, who sings jazzy pop to establish the retro mood of the show. Written by David Law, the central Ransom is Relative serial that winds through the show is another fun heroic take on history as charismatic Josh Scheibe plays a humble Mayor Daniel Hoan. This episode has Hoan helping his aid Oscar (Stephen Wolterstorff) get his daughter back from kidnappers looking to bring a key and iconic part of Milwaukee’s lakefront into private hands. Rob Schreiner is ruggedly gritty as hardboiled detective hero Jack Walker, who Hoan enlists to get Oscar’s daughter back. Carrie Johns gives a defiant edge to the victim Dotty. Andrea Roedel-Schroeder has engagingly sophisticated power as Dotty’s friend Liv, who is caught-up in the conspiracy. There’s a vulnerability to Liv that Roedel-Schroeder cleverly delivers to the stage. Roedel-Schroeder's a talented addition to the Cabaret Milwaukee ensemble. Back-up drama and comedy populate the edges of the action in between segments of the central story with Sarah Therese, Rebecca Sue Button and Liz Whitford Helin sing radio ad jingles as vintage ingenues. Between the tunes, they’re dealing with certain issues that continue to be tragically topical today. Laura Holterman and Michelle White continue to provide some of the most appealing provocative supporting material in the show as vintage radio homemaker Mrs. Millie and her thoroughly modern younger sister Billie. On the surface, it’s simply humor, but Holterman and White bring a hell of a lot of interpersonal characterization to the stage with Millie and Billie that strikes on a number of different themes. As with the best stuff in the show’s main serial, Holterman and White’s material cast the past in a light that resonates insightfully into the current world beyond the stage. Cabaret Milwaukee’s Ransom is Relative continues through Jan. 22 at The Astor Hotel on 924 E. Juneau Ave. For ticket reservations, visit Brownpapertickets.com Adam Bock’s A Small Fire plays out on dual tracks of drama and horror. Like any good drama and most good horror, the underlying power in the journey lies in its tribute to human survival. David Cecsarini directs a small, stellar cast of Milwaukee theatre icons in a very gripping story of a woman who is slowly becoming disconnected from the outside world. Mary MacDonald Kerr is deeply inspiring as Emily Bridges. Emily has a very strong sense of drive and direction about her. She’s the head of a construction company who deals with a million problems at once. Kerr deftly manages the task of maintaining an appealing and approachable presence in her portrayal of a person who is also very abrasive and totally immersed in work. As Emily, Kerr is, "gruff but lovable." Not many actors can truly pull that off. It’s impressive when it works. It’s particularly impressive here as it is the case that Emily gradually loses her senses over the course of 75 intermission-less minutes. She first loses her sense of smell. Her sense of taste goes with it. Then she loses her sight. Finally she loses he hearing. It’s never really explained what’s going on. Evidently doctors just don’t know. There’s very, very deep horror in that. Kerr sits in a room completely unable to see or hear anyone else in it. She’s had her senses to rely on her whole life. Now they’re gone. It’s difficult to imagine anything more horrifying than that. Jonathan Smoots plays her husband John. He's a nice guy who works in H.R. Smoots taps-into an endearing empathic energy as a man very much in love with his wife who is challenged to help her in whatever way he can. Smoots finds a valiant middle ground between powerlessness and restless compassion that serves the production well. Smoots’ heroism as John matched Kerr’s as Emily. John’s selflessness also speaks to a vulnerability that Smoots is able to articulate with breathtaking fluidity. No one seems more struck by John’s devotion to Emily than their daughter Jenny. Emily Vitrano wisely takes elements of compassion from Smoots and elements of driven self-sufficiency in the role of Jenny. There’s a very natural sense of family about the three actors and it has a lot to do with the way Vitrano links them all together. Her mother’s abrasiveness seems to have kept Jenny at a distance her whole life. She’s getting married to a man her mother doesn’t like. She’s concerned that her father’s devotion to her mother is unhealthy. Vitrano treads the delicate border between bitterness and love for her mother in a very sophisticated portrayal of someone trying to move on with her life as her mother’s falls apart. The family dynamic between Kerr, Smoots and Vitrano is given further definition by Mark Corkins in the role of Emily’s workplace assistant Billy Fontaine. Corkins summons an irresistible workin’ guy charm to the stage dynamic. What appears to be a minor supporting role early-on adds a striking depth to the story as Emily’s condition worsens. The drama plays out on a minimal stage co-designed by Rick Rasmussen and Cecsarini. It’s a very cleverly thought-out stage design that allows just enough detail to give the impression of Emily’s world as it slowly dissolves around her. Aaron Sherkow’s lighting design and Cescarini’s sound design profoundly punctuate Emily’s sudden losses of sensation with notable impact. It’s delicately finessed. Those moments of loss are never over-rendered with production elements. Bock’s script never leans-into them with a whole lot of dialogue. This is deeply terrifying in its own way. There’s no warning when losses occur...they just happen. The cast does a brilliant job of exploring the emotional impact of those losses. Next Act’s production of A Small Fire runs through Feb. 23 at the Next Act Theatre on 255 S. Water St. For ticket reservations and more, visit Next Act online. |

Russ BickerstaffArchives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed